Some of my ancient ancestors were Norse traders and raiders that explored and settled in an area near the Baltic Sea in what is now Russia and the Ukraine. After a few generations of intermarriage with the native Slavic tribes, they became known as the “Rus.”

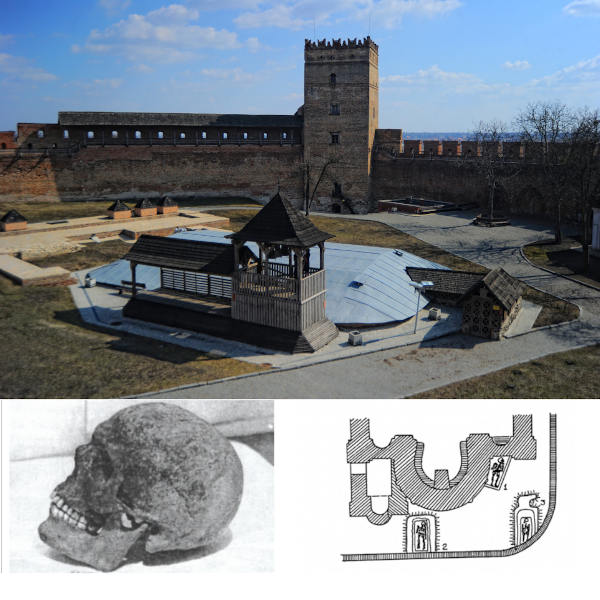

Prince Izjaslav Ingvarevych of Dorogobuzh

The individual with whom I share a genetic link was a man named Izjaslav Ingvarevych (Izjaslav, son of Ingvar”), a 13th century prince of Kiev. He was born about 1180, and he died on May 31, 1223, during the Battle of the Kalka River. He had a Mongol arrowhead in his skull, and various stab wounds on his bones.

His father was Prince Ingvar Yaroslavich (1152-1220), the Grand Prince of Kiev. In 1220, Izjaslav Ingvarevych was appointed Prince of Dorogobuzh in the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, which spanned much of present-day Ukraine and surrounding regions. Because of dynastic struggles, during this period, the Kievan Rus had been divided into separate principalities that were loosely organized.

Prince Izjaslav’s genome was sequenced as part of the largest Viking DNA study ever done. Population Genomics of the Viking World was published in Nature magazine on September 16, 2020. This six-year project was led by Professor Eske Willerslev, a Fellow of St John’s College, University of Cambridge, and director of The Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre, University of Copenhagen. Although Izjaslav was not a Viking, his genome was of interest to the study team as the travels, trading and raiding of Norwegian, Swedish and Danish Vikings had an enormous impact on the genetics and history of much of Europe and beyond, including Russia and Central Europe.

In 1989, Izjaslav’s skull was discovered in a tomb at Lutsk Castle, one of the most famous landmarks in the present-day city of Lutsk, Ukraine. Analysis of Izjaslav’s skeletal remains indicated that he died a violent death around the age of 30-40. Along with the carbon dating performed on both the skull and the tomb, the physical injuries match the description of Izyaslav being killed in battle.

The Battle of the Kalka River

The Battle of the Kalka River was fought between the Mongol army and a coalition of Rus principalities and their ally, the Cuman-Kipchak tribes. The Mongols were led by Jebe Noyan and Subutai Ba’atar, two of Genghis Khan’s most renowned military commanders. The Rus were under the joint command of Mstislav the Bold and Mstislav III of Kiev. Koten, a chieftain or khan, led the warriors of the Cuman-Kipchak federation. The battle was fought on May 31, 1223, on the banks of the Kalka River in present-day Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine, and ended in a decisive Mongol victory by the slaughter of the Rus.

The overconfident Rus military leaders marched their troops separately and hours apart from each other. Mstislav III of Kiev and his Cuman allies attacked the Mongols without waiting for the rest of the Rus army and were defeated. Several Rus princes were killed in the battle, including Izyaslav. Mstislav the Bold managed to escape the battle. The Mongols executed Mstislav of Kiev with the traditional Mongol caveat reserved for royalty and nobility: without shedding blood. Mstislav and his nobles were buried and suffocated under the Mongol general’s victory platform at the victory feast.

In his book, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, Jack Weatherford describes the battle: “The mounted princes of Russia sat astride their massive warhorses with their shiny javelins, glistening swords, colorful flags and banners, and boastful coats of arms. Their European warhorses had been bred for a massive show of strength—to carry the weight of their noble rider’s armor on the parade ground—but they had not been bred for speed or agility on the battleground…The Mongols overtook the ironclad warriors, and one by one killed the reigning princes of the city-states of Russia.”

Unlike several of his cousins, Izjaslav Ingvarevych fell in battle. He sustained wounds and may have been mutilated after death. Did he fight on resolutely or in despair, until an arrow obliterated all thought?

Izjaslav Ingvarevych’s Rus and Norse Ancestors

Izjaslav Ingvarevych can trace his ancestry (and mine?) back eight generations to the founder of the Rurik Dynasty. Rurik was a Varangian or Viking chieftain from Sweden who in the year 862 gained control of Ladoga, a trading post, and built the Holmgard settlement near Novgorod. It was the ruling dynasty of the Kievan Rus and its principalities and lasted to the death of Tsar Fyodor I in Moscow in 1598. Fydor was the son of Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich, commonly known as Ivan the Terrible.

Rurik and his descendants built an empire. Some of the more colorful ones prior to Izjaslav Ingvarevych include:

Vladimir Vsevolodovich “Monomakh” (1053-1125): A Grand Prince of Kiev, he was the son of Vsevolod I and Anastasia of Byzantium whose father some give as Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos. Eupraxia of Kiev, a half-sister of Vladimir, became notorious for her divorce from the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV on the grounds that he attempted a black Mass on her naked body. Numerous legends are associated with Monomakh’s name, including the transfer from Constantinople to Russia of the crown called “Monomakh’s Cap.” Vladimir was married three times. His first wife was Gytha of Wessex, daughter of Edith Swannesha and King Harold Godwinson of England who fell at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. (Another ancestor killed by an arrow!).

Grand Prince Sviatoslav Igorevich of Kiev (943-972) was a fierce warrior who fought continually with Slavic and Steppe tribes. He was betrayed and slain by the Pechenegs while crossing a series of cataracts. His skull was made into a drinking cup.

Saint Olga of Kiev (890?-969) was a Norse noblewoman married to Igor, son of Rurik. Her husband was brutally slain by a tribe called the Drevlians. After his death she ruled the Kievan Rus as regent on behalf of their son, Sviatoslav. She is known for bringing Christianity to the Rus, and for here bloody revenge on the Drevlians, burying alive one group of emissaries, and burning to death another group. A cunning politician and war leader, she kept the patrimony intact for succeeding generations.

This genealogical discovery by 23 and Me may have solved the origin of our mysterious Swedish ancestry. However, I don’t know yet if it is from the Scandinavian branch of the family or the Eastern European one.