It’s a thrill when a DNA discovery matches a family story.

A few years ago, I was swapping memories with my cousin, Donna, when she mentioned that her dad told her that we were descended from Eric the Red. It was one of the stories his grandfather, Carl Andersen, told him when he was a boy.

Several years ago I had my DNA analyzed by 23andMe. In 2024 they introduced “Historical Matches,” a premium service that will match you with historical figures in their database. They get the match from analyzing the DNA in their database with archaeological discoveries.

One of these matches turned up a genetic link with “Erik the Red’s Brattahild Villager VK184.” This person was among 13 men and two boys buried in a mass grave on the south side of a church built by Erik the Red’s wife, Thjodhild Jorundsdottir. The church was built in the early days of the Norse settlement of Brattahild. Archaeological excavations at the site revealed that high-status men (and some high status women) were primarily buried on the southern side of the church. Isotopic analysis suggests that some of those buried may have been immigrants from Iceland. Through DNA analysis, V184 was identified as genetically male.

Some people have thought that this church was the one referred to in Erik the Red’s Saga. According to the saga, Erik’s son, Leif the Lucky, introduced Christianity to Greenland around 1000 CE at the request of King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway. Erik refused to become a Christian, but his wife, Thjodhild, did and she built a church on their farm. The building was called “Thjodhild’s Church.” She had it situated some distance from the farmstead so as not to antagonize Erik. Her conversion caused tension in their marriage. The exact location of Erik the Red’s grave remains unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that Erik’s wife, Thjodhild Jorundsdottir, son Leif, Leif’s children, grandchildren and possibly other kinfolk were buried by the church.

Brattahild was Erik the Red’s estate in the colony named the Eastern Settlement. It was established about 986 CE in southwestern Greenland near the present settlement of Qassiarsuk. The site is about 60 miles from the ocean at the head of the Tunulliarfik Fjord. It was sheltered from ocean storms. The descendants of Erik the Red lived there until the middle of the 15th century, when the settlement was abandoned. The name Brattahild means “the steep slope.” Born in Norway around 950 CE, Erik Thorvaldsson’s red hair and fiery personality earned him the nickname, “Erik the Red.” Shortly after he was born, Erik’s family moved to Iceland after his father, Thorvald Asvaldsson, was banished from Norway for manslaughter. In 982 CE Erik was exiled from Iceland for similar reasons, pushing him to explore Greenland’s coast.

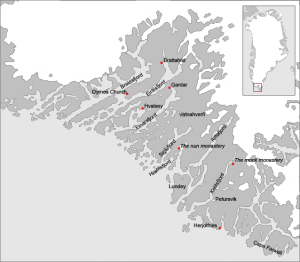

In the summer of 985 CE, Erik the Red left Iceland to colonize Greenland with 25 ships; 14 of which made landfall safely. The others were driven back to Iceland or wrecked. The settlers brought horses, sheep, cows, oxen and dogs. Two colonies were established: the Eastern Settlement and the Western Settlement, both on the east coast of Greenland. Some smaller settlements were in between. Archaeologists have identified the ruins of approximately 620 farms: 500 in the Eastern Settlement, 95 in the Western Settlement, and 20 in the Middle Settlement. The Norse population at its peak was probably between 2,000-6,000 people.

While he lived in Iceland Erik married Thjodhild Jorundsdottir, the daughter of Jorundur Ulfsson and Torbjorg “Ship-Breast” Gilsdottir. They had several children, including Leif Eriksson, Thorvald Eriksson, and Thorstein Eriksson. Erik’s daughter, Freydis Eriksdottir, may have been born of their union or by another woman. Leif was the only child buried at Brattahild. Thorvald was killed by natives in Vinland and buried there. His brother, Thorstein Eriksson, and his wife, Gudrid, set sail for Vinland to retrieve his brother’s body. The voyage was beset by storms and bad weather and they never reached Vinland. They turned back and were blown off course, landing in the Western Settlement 300 miles north of Brattahild. Thorstein perished that winter in an epidemic. Freydis Eriksdottir lived with her husband, Thorvald, in the community of Gardar (now Igaliku), about 10 miles away by boat from Brattahild (now Qassiarsuk). Gardar was the site of the first cathedral, built in 1126 CE, decades after Freydis had died. In 1944, when excavating the Gardar cathedral ruins, in an area that earlier housed a pre-Christian sacred area, archaeologists found the bodies of a man and woman. Some believe that they are the remains of Freydis and Thorvald. Under the same area are the skulls of 25 walrus and five narwhales. The sons of Erik the Red had accepted Christianity, but it is unclear if Freydis did.

The last recorded merchant ship reached Greenland in 1406. The captain, Thorsteinn Olafsson, stayed in Greenland for a few years and married Sigrid Bjornsdottir, in the church in Halsey on September 14, 1408. Two priests officiated and guests arrived from as far away as Iceland. They toasted the couple with mead and feasted on broiled mutton for three weeks. The account of their happy wedding is the last written record of the Norse Greenlanders. When Thorsteinn Olafsson left Greenland in 1410 he departed with the last news of the Eastern Settlement. It concerned a male witch, Kolgrim, who seduced a married woman through black magic. The woman, named Steinunn, was the daughter of Hrafn the Lawman. Steinunn became insane and died. Kolgrim was burned at the stake for using “love magic” to bend the woman to his will. Although there is no first-hand account of Norse Greenlanders living after 1410, analysis of the clothing buried at Herjolfsnes suggests contact was maintained with Norway and other countries for another 50 years, possibly longer.

Then, silence.

In 1721, Danish missionary Hans Egede asked the local Inuit about some Norse ruins, and the response was simply that the Norse themselves had left Greenland. Some archaeological findings indicate people in some farms starved to death; some Inuit stories described raids by the Inuit and white-skinned whalers (English, Basque) which killed men and carried off women and children as slaves. The Inuit preserved a cultural memory where they took some remaining women and children with them to save them from starvation and further raids. The Inuit said the Norse left in ships that looked like “boots” and never returned.