Richard Nason lived to be almost 90 years old. A rare achievement now, and even more so in the 17th century. He must have been wiry and resilient, carried along by a stubborn determination to live and prevail. He came by himself to Maine when he was a young man; no family member, cousin or nephew preceded or came after him. He built up his estate through his hard work and the work and support of his two wives. Richard Nason was a planter, surveyor, elected official, ensign in the militia, and ran a tavern. He had a role on the wharves at Pipe Stave Landing, an important shipping and ship-building site in what is now South Berwick, Maine. He also had some patronage and connections in England, Massachusetts Bay Colony or both for him to have been granted 200 acres of prime land. Luck and perhaps some good relations kept him and most of his family alive during the Abenaki raids on the Salmon Falls River area.

The last decade of Richard’s life – the 1690s – were filled with watchfulness, loss and death. There were conflicts with Puritans, Puritan authorities in Boston, raids by local Abenaki groups and their French allies; and even the terror of the Salem witch trials in 1692. Mercy Lewis, one of the accusers, was from the area, as was Rev. George Burroughs, a minister who was arrested and brought from Wells, Maine to Salem to be tried and hung as a witch. Burroughs’ traveled on a road close to the Nason homestead. It is known now as Witchtrot Road.

Two of Richard Nason’s sons were dead by the time he made his will in 1695. His son, Richard, was killed by an Abenaki warrior in 1675 or 1685 (date based on his wife remarrying in 1687) although some accounts cite the Salmon Falls Raid in 1692. Jonathan Nason was killed by his brother, Baker, with a canoe paddle in 1690/91 when they were traveling on the Piscataqua River. Baker claimed self-defense. A Court of Oyer and Terminer declined to prosecute. Another son, Joseph, had left for Nantucket and became a Quaker. Henry Child, the first husband of Richard’s daughter, Sarah Nason, was killed by Abenakis on September 25, 1691. She married John Hoyt on November 10, 1695, only a few months before her father died.

Several of Richard Nason’s grandchildren were captured by Abenakis and taken to Quebec to be sold as servants. Richard Nason III was seven or eight years old when he was captured. He was baptized “Jacques Ritchot,” and never returned. Sarah Nason, the daughter of Benjamin Nason, was kidnapped and taken to Canada in 1694. She was ransomed and returned several years later.

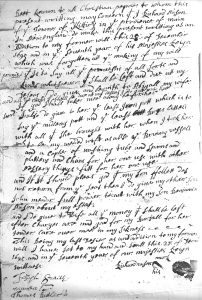

We can study Richard Nason’s will, agreement, codicil and inventories to glean information on his economic status and his relationships with various people. One person he mentions continually is his second wife, Abigail Follett. It is clear that he loves her very much, is concerned for her welfare, and is grateful for the “tender care” she took of him in the last years of his life.

Richard Nason was married to his first wife, Sarah Baker, from the 1630s to 1663/4. She bore him all his children. When she died, she left him with several young children and teens. They needed a mother, and Richard needed a woman with domestic and household management skills. He married the widow Abigail Follett around 1664. She was probably 15-20 years younger than Richard. Abigail’s first husband, Nicholas Follett, was a cooper and a mariner. They had at least four children together and probably lived in Portsmouth or Dover, New Hampshire. She brought children to the marriage, and at least two of them, Nicholas and Sarah, grew up in Richard’s household. This blended family lived together until the children married and left. Eventually Richard and Abigail Nason lived with his son, Benjamin, and Benjamin’s family. Richard’s son, Baker Nason, lived close by and helped support his father and his father’s wife.

Richard Nason’s will is dated July 14, 1694, and was probated on March 15, 1996/7. He was ill and made the will “under the infirmities of old age.” Language in the document notes that it was written in the sixth year of the reign of King William III and Queen Mary. Richard uses the Abenaki name of “Newchewanack” to describe the place where he lives. In the rest of the document, the place is named “Kittery.” I’m pretty sure Richard always called his home area “Newchewanack,” the place name used by Abenakis who farmed and fished there. The native people probably taught him that word and how to plant “Indian corn.”

Richard states that he is “penitent from the bottom of my hart for my Sins Past most humbley Desiring forgiunesse for the Same…” A forthright and outspoken man, I doubt any of his challenges to the Puritan government in Boston, or their sympathizers in Maine provoked a last-minute regret. The expression also could have been a stock phrase from the scribe. However, outspoken, decisive people may feel regret after seeing the impact of their actions. Since Richard out-lived many neighbors and several of his children, he could not express his remorse to them.

Richard Nason’s July 14, 1694 will; September 20, 1694 agreement with his sons Benjamin and Baker; and December 28, 1695 codicil all provide a window into his relationships with family members—his own children with his first wife and his relationship with his second wife and her children. Richard Nason was most solicitous of his wife, Abigail. It is obvious that he loved and cared for his second wife very much. If he married her around 1664, they had been together for almost 30 years when he died. He was about 20 years older, marrying the widow Abigail Follett when he was in his late 50s and she was in her late 30s or early 40s. They did not have any children together, but she must have helped raise several of Richard’s and Sarah Baker’s children. Richard also helped raise some of Abigail’s children, probably Sarah and Nicholas. Abigail (Brewer) Follett may have come from Stratford-Upon-Avon, Richard Nason’s birthplace. Abigail would have been a toddler or small child when Richard left for Massachusetts Bay Colony in his early 20s.

Richard named his wife, his surviving children, and two of Abigail’s children in his will as equally sharing in his estate. They are listed in birth order, males first, then females, then Abigail’s children: John Nason, Joseph Nason, Benjamin Nason, Baker Nason, Sarah (Nason) Child, Mary (Nason) Witham, Nicholas Follett, and Sarah (Follett) Meader. He first provides for his wife with specific bequests and annuities, and then divides the remainder of the estates equally between his children and his “children-in-law. “It is clear that Abigail’s son and daughter are as dear and important to him as his own sons and daughters.

Richard returned to his wife all the property she brought to their marriage. He also granted her “one of my best beds and furniture belonging unto it and two Chests and Eight pounds in Silver Current Money of New England…one-third of all the Indian corn.” He directed his heirs to “pay unto my sd wife Twelve pounds in money yearly for her maintenance during her Life.” Richard did not include the wives or children of his deceased sons, Richard and Jonathan. There is no mention of Charles or Dover Nason (if they were alive or even existed.) He also did not include Abigail’s two other sons, Philip and John Follett.

Richard names “my son Benjamin Nason and Nicholas Follet to be my Executors both or Either of them in Case of Mortality or absence at sea.” It is clear from the directives in his will that Richard Nason was fond of Nicholas Follett and thought very highly of him. Nicholas was born about 1653, so he was around 10 years old when he came into Richard’s household. Follett lived in Portsmouth and made his living at sea. “Nicolas Follett, Commander of the Brigantine “Friends of the Endeavor,” 25 tons from Barbados,” was noted on a log of incoming vessels into Portsmouth on September 17, 1692. Like Richard Nason, Follett was also very active in his community and the political structure. He was a representative to the New Hampshire Constitutional Convention in Portsmouth on January 24, 1690. He was a signer and a strong advocate of the “Address of the New Hampshire inhabitants asking for Equal Privileges with Massachusetts” on August 10, 1692. Follett died in the Bay of Campeche in the Gulf of Mexico during April 1700.

On September 20, 1694, two months after his will was signed, Richard executed an agreement with his sons Benjamin and Baker deeding the Pipe Stave Landing homestead to them provided they continued to support and take care of Richard and Abigail until their deaths. He deeded the land with the consent of Abigail. Both signed with their “mark.” Since Richard’s estate included “a parcel of old bookes,” and he functioned in several official capacities, I find it hard to believe that he couldn’t write his name. Perhaps he had an old injury or wound that impeded his writing? One of the witnesses was his neighbor, Martha Lord. This was unusual, and perhaps another window on Richard’s personality and values, since women were considered “less than” men at that time with less legal standing.

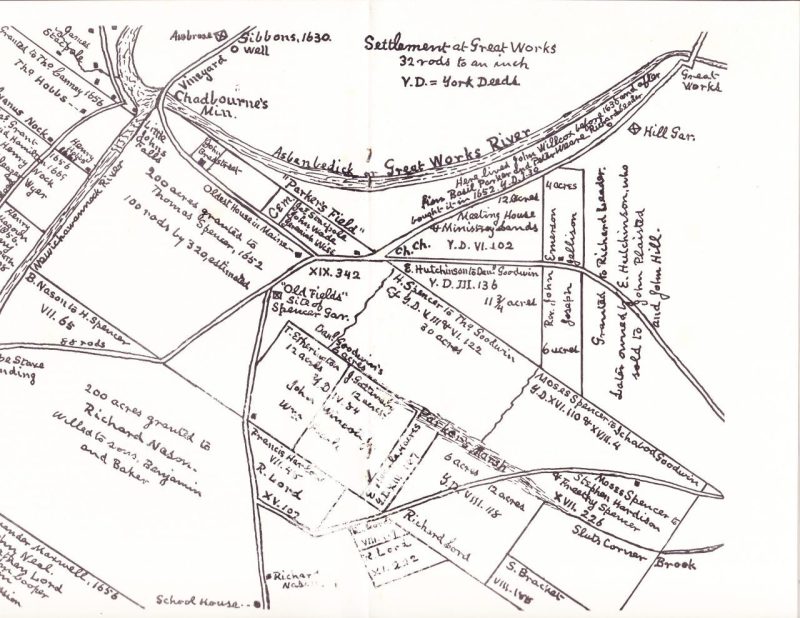

He described his property: “…all my housing, outhousing, barns and lands, being my homestall of 200 acres, besides the pastures bounded on the north with the lands that were the late Thomas Spencer’s deceased, and on the west by the tide river, and on the south with the land of the Widow Lord, and bounded on the east by the town commons, together with all the other outlands and meadows…and being all of them in this town of Kittery…” In addition to land and buildings, he had six cows, six calves, four oxen, twenty-seven sheep and his horse.

He was extremely detailed and precise in his instructions on what he expected his sons to provide. If Richard and Abigail wanted their own house, it needed to be 26 or 28 feet long and 18 feet wide with a “good chimney.” He wanted to choose the cow whose milk he wanted; two ewe lambs each year; provide firewood and keep the fire burning; “such garden fruit and tobacco as they have occasion for,” and allow them some of the fruit from his two apple trees. It was touching to see that he was fond of his apple trees. Until 2023 when it was cut down, an ancient apple tree stood close to the parking lot of the Hamilton House in South Berwick, Maine. This is the spot where Richard Nason purportedly lived at Pipe Stave Landing. I like to think that the old tree was the descendant of the apple trees Richard Nason planted.

It’s odd that Richard Nason’s oldest living son, John Nason, was not included in the division of the Nason homestead. In his old age, Richard and his second wife, Abigail, lived with his son, Benjamin and his family at the family homestead. Baker Nason and his family lived close by, as did John Nason and his family. Was it a case of family members not getting along? In 1713 – roughly 17 years after Richard Nason died, Benjamin and Baker sold to John a full half of the property, which, according to the deed, Richard had intended to convey to John, but failed to execute a deed before his death. From the deed text John had already built a house and lived on the property. Since Richard Nason had been very clear in his wishes and wants, I’m sure that the omission was deliberate. The other older son, Joseph, may have already moved to Nantucket. The two brothers may have waited until Abigail Nason was dead before selling the land to their older brother. (York County, Maine, Deeds, Book 7, Page 259).

Richard Nason added a codicil to his will on December 28, 1695. It includes more specific household goods to go to his wife. He praises Abigail “for her tender Care over me in my Sickness.” He also names Sarah Follett’s husband, John Meader, to act as co-executor in the event Nicholas Follett was lost or gone at sea. “And if it should please God that my son Follett do not return from the Seas then I do give my other son John Meader full power to act with my Son Benjamin Nason about my Estate.”

Richard Nason died between December 29, 1695 and January 3, 1696. He was 89 and ½ years old. His wife, Abigail, was probably in her late 60s. She lived for another 10-15 years after Richard’s death. An online search for “Abigail Brewer Follett” indicates she lived in Dover, New Hampshire at the time of her death in her early 80s.

After Richard’s death, two inventories of his property were completed. “An inventory of that parte of the Estate of Richard Nason deceased whc is in Benja Nason custodee att the dwelling house where ye deceased lived. The inventory was done 12th March 1696/7 by the order of Benja Nason…” Thee was a large inventory of household goods and furniture, “4 Gunns.” Lots of cloth, “sheeps Wolle” and tools for weaving. There was a second inventory “part of Richard Nasons estate at Portsmouth.” These items were in the custody of Nicholas Follett. This inventory was taken the 4th day of January 1696/7. One of the items mentioned was a “parcel of old bookes.” Nicholas Follett acknowledged that “some money whc was left in my possession and wiled to his wife as appears by his last will.”

Richard Nason is buried with his neighbors in the Old Fields Burying Ground on Vine Street near Old Fields Road and Brattle Street in South Berwick, Maine. It was the main burial place of the town’s first English settlers and one of the oldest cemeteries in the U.S. dating from the 1600s. A photo of the site in the late 1800s shows the site clear of trees. When we visited in 2023, the cemetery lay in a forest of tall, thick white pine. Many of the graves are no longer visible and only fragments of headstones remain. It is a beautiful spot. As I walked among the faded gravestones and half-buried stone markers, I was struck by what a quiet and peaceful place Pipe Stave Landing is now—a stark contrast to the tumult, danger and violence in Richard Nason’s time.

Thank you for your research!

Elizabeth, thank you so much for your kind comment. I believe I got a good sense of the man from visiting Pipe Stave Landing, reading his wills and directives, understanding his contentious history with Boston and area Puritans and seeing an actual garrison house in Dover, NH. The part I enjoyed the most was seeing the ancient apple tree near where Richard’s original house once stood. I understand his love for apple trees. Thanks again for writing.

How great to fine find these articles and learn about my earliest ancestor in New England. My late grandmother, Dorothy Nason, would have appreciated them very much. I’ll pass them along to my father. I live in Maine, so I’ll have to make a trip to Pipe Stave Landing and Old Fields. Thank you so much for your research!

David, thanks so much for your kind words. It was great to hear from you. It was a very interesting experience for me to try to imagine Richard Nason by walking the land, reading about his various scrapes and battles with authorities, and speculating on his values and relationships through his wills and codicils. I think we have a pretty remarkable ancestor.